How can I achieve flow? How can I learn to live in the moment?

- Amelia Marriette

- Apr 20, 2020

- 5 min read

My head is not racing at all today, and although it is not tranquil as it was when I walked in the snow, I feel as I walk a calmness seeping into me. I do not feel the need to plug myself into any exterior distraction; I have not downloaded any podcasts; I have nothing prepared. But it is easier now that it is late spring, and there are so many sounds to enjoy: birdsong galore, and the crickets’ orchestra moves between a restrained classical score to one of classic rock. I imagine them as out-of-control rock stars with their own noisy thrill of fans. Insects are buzzing; meltwater, from the recent heavy snowfall at the end of April, tumbles and cascades over rocks; and underscoring all these brash sounds there is the pleasant sound of the leaves in the trees rustling quietly in the breeze. But the cows, at least, are very quiet. Most are lying with their young calves in the sun, seemingly happy and contented.

The walk soon becomes an absorbing experience, and my mind manages to enter a state of flow.[i] In 1975, the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi both recognised and named the psychological concept of flow. I am amazed when I realise that I have achieved this feat at last; I completely lose all track of time; I am fully immersed in an energised feeling of focus and involvement. I think it only happened by walking more slowly and rhyming my footsteps with the calling and singing birds. I did not realise before just how difficult it is to learn to live in the moment, but because of this project, I am beginning to unlearn bad habits from the past. This is not an outcome I expected, but it is one I would certainly have wished for.

There is snow on the Koralpe, and it is still a thick icing of brilliant white, but it only crowns the top. The Karawanken are also snow-capped but are lost in haze, which is quite usual. I watch for several long minutes, not daring to move, as a copper-red kestrel on a telegraph wire eyes his prey and then swoops to kill, flying to a more distant perch to consume his catch.

I reach the apple tree and discover that the apple blossom is now at its very best. Paying attention to the shape of the spring flowers, I begin to appreciate and understand that the apple tree is part of the rose family, and although short-lived the blossom flowers are truly as beautiful as any flowering rose.[ii] I suddenly have the impulse to lean in and smell the blossom; it does smell like roses, with perhaps a little extra vanilla. It has never occurred to me to do this before. The apple tree is now a symphony of colour and fecundity, with tight dark pink buds, snowy-white petals. In the centre of the petals the creamy-yellow, pollen saturated stamens, while around the blossom the luxuriantly green leaves sing out.

As I study the blossom closely, I realise that the whole tree is a throbbing mass of bees; it’s so noisy that at first, I think there must be a moped in the vicinity. The blossom is offset by patches of yellow and green lichen which have wonderfully textured, erupting surfaces, and I touch them very gently so as not to harm them in any way. The lichen is especially apparent on the shadier side of the tree, where the trunk is facing the prevailing wind and rain, for lichen and mosses are moisture-loving and require this extra dampness. Although it has a firm hold it is not harming the tree; in fact, it indicates that the air here is clean, as lichens only thrive in clean, fresh air. Today I collect a small fallen branch from the apple tree, one that displays a fine example of the green lichen. I am hoping that Katie will not be able to resist forging and beating some metal, inspired by these growth patterns, perhaps adding verdigris to copper to try and mimic this magical mossy-green colour.

The farmers have mowed many of the dandelion fields, and this harvest will be used as animal fodder. In so doing they have left wonderful swathes of verdant green fields which look perfect in the late evening sun. The stripes of the newly-mown fields, in fact, look like a watercolour or a linocut, perhaps depicting manicured cricket fields, although a ball game would be difficult if not impossible due to the steep undulating nature of the landscape. The whole scene reminds me of the delicately pale, luminous watercolours of Eric Ravilious, who was a great inspiration to my father.

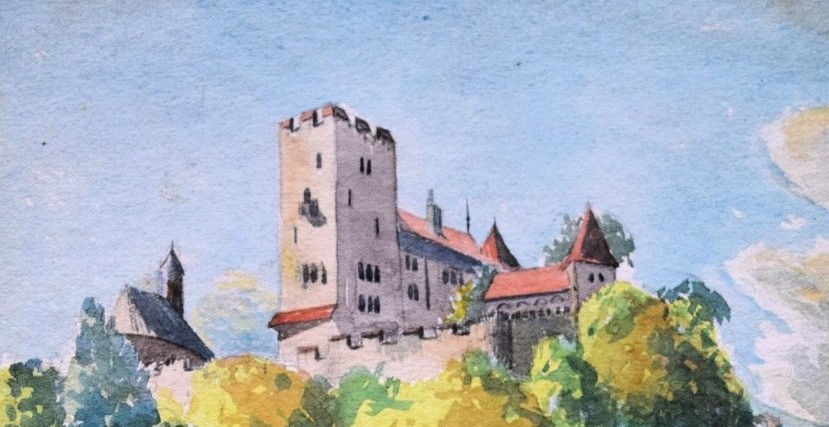

Ravilious grew up in East Sussex, and would walk across the South Downs, an area now designated as a National Park, the place which most inspired him. The South Downs, although quite low lying (rising only to 889 feet above sea level), provided Ravilious with the views he seemed to most favour; he loved to survey a scene from a high vantage point. While other artists shunned the everyday and the banal, Eric Ravilious recorded daily life: English harvests, or old and broken machinery lying abandoned in fields. He was also a master at depicting the tillage of the land, the striations made by the plough or tractor.[iii] My father also found beauty in the simple furrows made by a tractor, and I have an early watercolour on which he has written on the reverse: ‘A View from my Billet, Downham Market, April 45.’ It’s clear in this small piece that he spent as much time patiently painting the furrows and carefully mixing cobalt blue and burnt umber to get just the right brown earth colour, marking each ploughed line meticulously. I can imagine that both Ravilious and my father standing next to me, admiring as I am now, the artful work of the farmer.

I have spent many hours looking at this particular Austrian landscape - nineteen walks already completed - and I am fascinated by the ever-changing states of the land. Watching it being perpetually altered and manipulated has served only to increase my fascination. Collectively we no longer have the vocabulary to explain all these different states, but such words did once exist and were in common usage. Take ‘sillion’, ‘vores’ and ‘warp’ as examples. ‘Sillion’ is a poetic term meaning ‘the shining curved face of the earth recently turned by the plough.’ ‘Vores’, originating from Devon, means the furrows made by a plough. Having lived in Devon, I can see how when spoken with a Devon burr, furrows easily becomes vores. And lastly, ‘warp’ is the soil between the furrows, a word, in fact, that originates from Ravilious’ Sussex.[iv]

I am normally happy to spend time taking photographs, and I do not normally consider it to be a poor relation of the other visual arts, but today I feel that a paintbrush and paints would be able to render the scene before me in a way that the camera cannot.

Endnotes.

[i] “The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times… The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile”. https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/mihaly-csikszentmihalyi-father-of-flow/

[ii] With over 2,500 species in more than 90 genera, the rose family Rosaceae, which includes among its number: apples, pears, quinces, medlars, loquats, almonds, peaches, apricots, plums, cherries, strawberries, blackberries, raspberries. https://www.britannica.com/topic/list-of-plants-in-the-family-Rosaceae-2001612

[iii] See, for example, Eric Ravilious’s, Mount Caburn, 1935. http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=246073

[iv] Robert Macfarlane, Landmarks, Penguin Books, 2015, Glossary VII, Fields and Ploughing, page 258.

This is an extract from Walking into Alchemy: The Transformative Power of Nature by Amelia Marriette. See www.ameliamarriette.com for more information. Buy the e-book for only 1.99 Euros. £1.84 or $2.00 dollars.

The image is a watercolour by my father Leonard Eason. "RAF Billet, Downham Market, Norfolk. April 12th, 1945." He spent much time looking closely at nature and note here the attention to detail in the furrows - vores - made by the plough.

Comments